Dear aspirants,

- https://www.sscadda.com/2018/12/current-and-electricity-notes-for-rrb-alp.html

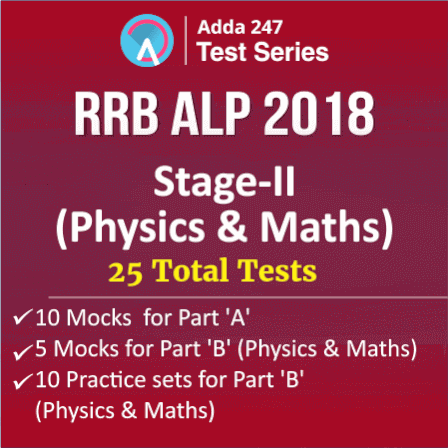

Looking forward to providing you the best apt study content for every government exam at no cost thus making access to the exam content convenient for you, SSCADDA is available once again to assist you thoroughly in Railway ALP Stage 2 Exam 2018 where the motive is to enable you with Physics detailed notes on definitions, concepts, laws, formulae, rules and properties, important from the exam point of view. Stay in tune with SSCADDA to utilize the remaining time for Railway ALP Stage 2 and maximize your practice skills.

ELECTRIC CURRENT

Electric current is expressed by the amount of charge flowing through a particular area in unit time. It is the rate of flow of electric charges.

If a net charge Q, flows across any cross-section of a conductor in time t, then the current I, through the cross-section is-

I = Q/t

The SI unit of electric charge is coulomb (C), which is equivalent to the charge contained in nearly:

The electric current is expressed by a unit called ampere (A). One ampere is constituted by the flow of one coulomb of charge per second, that is, 1A = 1 C/1 s.

EXAMPLE: A current of 0.5 A is drawn by a filament of an electric bulb for 10 minutes. Find the amount of electric charge that flows through the circuit.

Solution:

We are given, I = 0.5 A; t = 10 min = 600 s.

As Q = It

= 0.5 A × 600 s

= 300 C

ELECTRIC POTENTIAL AND POTENTIAL DIFFERENCE

The electric potential difference between two points in an electric circuit carrying some current is the work done to move a unit charge from one point to the other;

Potential difference (V) between two points = Work done (W)/Charge (Q)

V = W/Q

The SI unit of electric potential difference is volt (V), named after Alessandro Volta (1745–1827), an Italian physicist. One volt is the potential difference between two points in a current carrying conductor when 1 joule of work is done to move a charge of 1 coulomb from one point to the other.

The potential difference is measured by means of an instrument called the voltmeter. The voltmeter is always connected in parallel across the points between which the potential difference is to be measured.

ELECTRIC CURRENTS IN CONDUCTORS

In other materials, notably metals, some of the electrons are practically free to move within the bulk material. These materials, generally called conductors, develop electric currents in them when an electric field is applied.

In solid conductors:

(a) When no electric field is present- The number of electrons travelling in any direction will be equal to the number of electrons travelling in the opposite direction. So, there will be no net electric current.

(b) If an electric field is applied- An electric field will be created and is directed from the positive towards the negative charge. They will thus move to neutralize the charges. The electrons, as long as they are moving, will constitute an electric current.

OHM’S LAW

Imagine a conductor through which current I is flowing and let V be the potential difference between the ends of the conductor.

Ohm’s law states that:

V ∝ I

or, V = R I;

where the constant of proportionality R is called the resistance of the conductor. The SI units of resistance is ohm, and is denoted by the symbol Ω.

The resistance of the conductor depends-

(i) on its length,

(ii) on its area of

cross-section, and

(iii) on the nature of its material.

LIMITATIONS OF OHM’S LAW

(a) V ceases to be proportional to I

(b) The relation between V and I depends on the sign of V. In other words, if I is the current for a certain V, then reversing the direction of V keeping its magnitude fixed, does not produce a current of the same magnitude as I in the opposite direction

(c) The relation between V and I is not unique, i.e., there is more than one value of V for the same current I A material exhibiting such behaviour is GaAs.

ELECTRIC CURRENT

Electric current is expressed by the amount of charge flowing through a particular area in unit time. It is the rate of flow of electric charges.

If a net charge Q, flows across any cross-section of a conductor in time t, then the current I, through the cross-section is-

I = Q/t

The SI unit of electric charge is coulomb (C), which is equivalent to the charge contained in nearly:

6 ✖ 10¹⁸ electrons

EXAMPLE: A current of 0.5 A is drawn by a filament of an electric bulb for 10 minutes. Find the amount of electric charge that flows through the circuit.

Solution:

We are given, I = 0.5 A; t = 10 min = 600 s.

As Q = It

= 0.5 A × 600 s

= 300 C

ELECTRIC POTENTIAL AND POTENTIAL DIFFERENCE

The electric potential difference between two points in an electric circuit carrying some current is the work done to move a unit charge from one point to the other;

Potential difference (V) between two points = Work done (W)/Charge (Q)

V = W/Q

The SI unit of electric potential difference is volt (V), named after Alessandro Volta (1745–1827), an Italian physicist. One volt is the potential difference between two points in a current carrying conductor when 1 joule of work is done to move a charge of 1 coulomb from one point to the other.

The potential difference is measured by means of an instrument called the voltmeter. The voltmeter is always connected in parallel across the points between which the potential difference is to be measured.

ELECTRIC CURRENTS IN CONDUCTORS

In other materials, notably metals, some of the electrons are practically free to move within the bulk material. These materials, generally called conductors, develop electric currents in them when an electric field is applied.

In solid conductors:

(a) When no electric field is present- The number of electrons travelling in any direction will be equal to the number of electrons travelling in the opposite direction. So, there will be no net electric current.

(b) If an electric field is applied- An electric field will be created and is directed from the positive towards the negative charge. They will thus move to neutralize the charges. The electrons, as long as they are moving, will constitute an electric current.

OHM’S LAW

Imagine a conductor through which current I is flowing and let V be the potential difference between the ends of the conductor.

Ohm’s law states that:

V ∝ I

or, V = R I;

where the constant of proportionality R is called the resistance of the conductor. The SI units of resistance is ohm, and is denoted by the symbol Ω.

The resistance of the conductor depends-

(i) on its length,

(ii) on its area of

cross-section, and

(iii) on the nature of its material.

LIMITATIONS OF OHM’S LAW

(a) V ceases to be proportional to I

(b) The relation between V and I depends on the sign of V. In other words, if I is the current for a certain V, then reversing the direction of V keeping its magnitude fixed, does not produce a current of the same magnitude as I in the opposite direction

(c) The relation between V and I is not unique, i.e., there is more than one value of V for the same current I A material exhibiting such behaviour is GaAs.

No comments:

Post a Comment